Tuesday, June 27, 2006

Sunday, June 25, 2006

Apologies…

We greatly appreciate the e-mails we have received and the comments posted on this blog. Unfortunately, its been impossible to respond to the e-mails at this point. Power rationing disables the internet from sun-up to sundown, and we are using the internet connection at someone else’s house. So typically we have time to post a blog, but little more. But we are getting everyone’s messages; thank you so much!

Language school has been a great blessing. Language allows you to learn culture as well. For example, whenever you see an older person here, you say “Shikamoo”. There response is “marahaba”. Language books don’t even try to translate this.

Dr. Salala explained the meaning behind this expression. When you say Shikamoo, you are saying “I accept you as a parent”. Marahaba means, “I will care for you like my children”. Culturally, this is more true than you can imagine.

Also, please pray for us and our neighbors here in Mwanza. Many people close to us are dealing with malaria right now. While medicine is available, many people can’t afford it, and even when purchased, it doesn’t prevent people from a few miserable days of high fevers, chills, headaches, and body pains.

If the picture loads, it is Josiah with the first lizard he has caught here. The first 500 got away.

Wednesday, June 21, 2006

Father’s day.

Truth be told, we were completely ignorant of Father’s day until it was upon us. There are no Hallmark stores here to remind us of such holidays, and, though I have watched a few World Cup games on Tanzanian TV, the commercials are for the following items:

Coca-cola: Everyone speaks football!

Voda-com: sappy emotional commercials for a cell-phone company (like our phone commercials from the 80’s… reach out and touch somebody stuff)

NBC Bank: Their ATM’s are everywhere! (funniest commercials I’ve seen in years)

Anyways, this father’s day has been special because I have had some unique time with Josiah. We are watching the world unfold before his eyes. Some unique experiences of late include:

Josiah’s first Dala-Dala ride. The Dala-Dala is the Tanzanian bus system. The basic premise is that by maximizing seating capacity in a tiny, beat up vehicle, you can make a profit despite gas at $5/gallon and fares at $.20/passenger. On Josiah’s inaugural ride, on a trip back home from the central market, he had 25 close friends in a minivan sized vehicle. And I mean close. Normally opposed to personal space infringement, Josiah did not seem to mind the lack of space, though he was bewildered at his inability to determine which of the 25 other passengers was driving. His view was limited.

(note: Charity wanted to add that it was also Elijah’s first dala-dala ride. He didn’t care about drivers, though.)

Josiah’s first Mchezo. The Mchezo is the traditional Sukuma dance and drumming ceremony. We watched two dance troupes in the village of Bujora in the first day of a three-day festival that builds in intensity as the days progress. While the dancers were the main show, Josiah also garnered much attention. While people may see the occasional white aid worker, they aren’t used to toddlers with long, curly hair, and many made sure to touch it for themselves. Josiah was a good sport; wherever Josiah went, a crowd went with him. He played hard with the others, became covered in dirt, and even took a turn on some of the spare drums.

Josiah’s first language class. Actually, it was my first class, but Josiah asked to join me. He played and colored while Dr. Salala taught greetings until 9:30 pm. Greetings are incredibly important here; social courtesies are paramount in a relational culture, and I learned about 50 greetings that have nothing to do with gaining information, but building relationships. Josiah picked up on some greetings himself. He has been saying, “Hamjambo”, and “habari asabuhi” today.

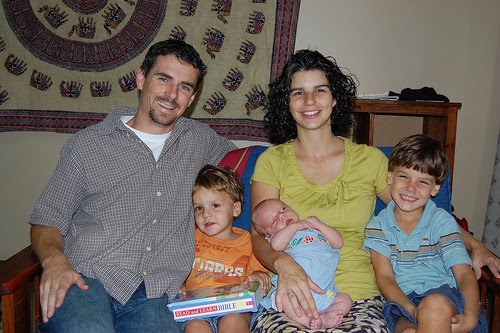

Nothing fills a father with more pride than a loving, wonderful family. I know of no one more blessed than I.

(note: the picture is from another website, as we are currently unable to upload our own pictures. But if you click on the picture, it may take you to a site to learn more about Sukuma dance.)

Truth be told, we were completely ignorant of Father’s day until it was upon us. There are no Hallmark stores here to remind us of such holidays, and, though I have watched a few World Cup games on Tanzanian TV, the commercials are for the following items:

Coca-cola: Everyone speaks football!

Voda-com: sappy emotional commercials for a cell-phone company (like our phone commercials from the 80’s… reach out and touch somebody stuff)

NBC Bank: Their ATM’s are everywhere! (funniest commercials I’ve seen in years)

Anyways, this father’s day has been special because I have had some unique time with Josiah. We are watching the world unfold before his eyes. Some unique experiences of late include:

Josiah’s first Dala-Dala ride. The Dala-Dala is the Tanzanian bus system. The basic premise is that by maximizing seating capacity in a tiny, beat up vehicle, you can make a profit despite gas at $5/gallon and fares at $.20/passenger. On Josiah’s inaugural ride, on a trip back home from the central market, he had 25 close friends in a minivan sized vehicle. And I mean close. Normally opposed to personal space infringement, Josiah did not seem to mind the lack of space, though he was bewildered at his inability to determine which of the 25 other passengers was driving. His view was limited.

(note: Charity wanted to add that it was also Elijah’s first dala-dala ride. He didn’t care about drivers, though.)

Josiah’s first Mchezo. The Mchezo is the traditional Sukuma dance and drumming ceremony. We watched two dance troupes in the village of Bujora in the first day of a three-day festival that builds in intensity as the days progress. While the dancers were the main show, Josiah also garnered much attention. While people may see the occasional white aid worker, they aren’t used to toddlers with long, curly hair, and many made sure to touch it for themselves. Josiah was a good sport; wherever Josiah went, a crowd went with him. He played hard with the others, became covered in dirt, and even took a turn on some of the spare drums.

Josiah’s first language class. Actually, it was my first class, but Josiah asked to join me. He played and colored while Dr. Salala taught greetings until 9:30 pm. Greetings are incredibly important here; social courtesies are paramount in a relational culture, and I learned about 50 greetings that have nothing to do with gaining information, but building relationships. Josiah picked up on some greetings himself. He has been saying, “Hamjambo”, and “habari asabuhi” today.

Nothing fills a father with more pride than a loving, wonderful family. I know of no one more blessed than I.

(note: the picture is from another website, as we are currently unable to upload our own pictures. But if you click on the picture, it may take you to a site to learn more about Sukuma dance.)

Monday, June 19, 2006

Street children and contaminated water…

Friday provided the opportunity to meet and hang out with Jonathon, a former streetchild. Jonathon was selling various postcards that he had made himself. It is his only income.

Jonathon learned English through a program in Mwanza that ministers to street children, which made the entire conversation possible. Though I encounter dozens of street children each day, most only know enough English to say “give me money.” Having an extended conversation was a true blessing.

Jonathon became a street child as a teenager after his mother died; since his father died earlier, he was free to leave his home and travel to Mwanza. Others become street children when their parents succumb to alcoholism, and tell their children to provide for themselves. Perhaps as many as half are simply runaways, who enjoy the freedom of traveling around with friends, scrounging for moneys, buying cigarettes and alcohol.

Orphans and unwanted children are not a new feature of Tanzanian culture. Families, villages, and tribes always found a way to care for orphans, and they ensured that everyone lived up to his or her responsibility to the group.However, what has changed is the unraveling of traditional society caused by the introduction of western politics, materialism, and individualism. Tribe and family used to come first. Increasingly, it is self.

Anyways, Jonathon struggles to get by, no longer living on the streets, but making enough money to rent a room in a squatter house ($5/month). Friday was a good day, as I bought five postcards; there was even enough money for him to buy some coffee from a traveling vendor ($0.04 for three cups). He likes it black, strong enough to keep him up at night while he draws new postcards.

I do feel like I was able to help him in one other practical way. One reason Jonathon likes to drink coffee is that the water is boiled, and thus purified. Jonathon, like all the residents of Mwanza, has no access to inexpensive, clean drinking water. Here are his options:

1. Buy bottled water. $0.25/liter is not much for water (Dasani, even!), but when you make about a dollar a day, the cost is prohibitive.

2. Boil water. Using city water, which is probably within 50 yards of his room, and boiling for 15 minutes, Jonathon will have water free of pathogens, but firewood is not cheap, and the smoke has long-term side effects on vision.

3. Walk to the brewery for free, purified water. But it is about a ten mile walk, which is quite hard when you will be carrying gallons of water back. Many people, however, do this daily.

4. Take a chance on city water. Most people do this from time to time. This is a major source of illnesses like typhoid, belharzia, and amoebas. And, over time, these can take a toll on one’s kidneys, eventually leading to kidney failure. (see post from last week). And the medicine cost adds up, too.

I shared with Jonathon one more option: Solar distillation. By refilling a clear water bottle with city water and setting it in a location with strong sunlight for 6 hours, over 99.99% of pathogens are killed. The UV radiation, which penetrates the plastic and radiates the water, does the work for you. Check out www.sodis.ch for more details. Jonathon seemed excited to give this a try. One of many things we will discuss in the future.

(I must give credit to Harding University School of World Missions, especially Oneal Tankersley, who first exposed us to solar distillation)

Friday provided the opportunity to meet and hang out with Jonathon, a former streetchild. Jonathon was selling various postcards that he had made himself. It is his only income.

Jonathon learned English through a program in Mwanza that ministers to street children, which made the entire conversation possible. Though I encounter dozens of street children each day, most only know enough English to say “give me money.” Having an extended conversation was a true blessing.

Jonathon became a street child as a teenager after his mother died; since his father died earlier, he was free to leave his home and travel to Mwanza. Others become street children when their parents succumb to alcoholism, and tell their children to provide for themselves. Perhaps as many as half are simply runaways, who enjoy the freedom of traveling around with friends, scrounging for moneys, buying cigarettes and alcohol.

Orphans and unwanted children are not a new feature of Tanzanian culture. Families, villages, and tribes always found a way to care for orphans, and they ensured that everyone lived up to his or her responsibility to the group.However, what has changed is the unraveling of traditional society caused by the introduction of western politics, materialism, and individualism. Tribe and family used to come first. Increasingly, it is self.

Anyways, Jonathon struggles to get by, no longer living on the streets, but making enough money to rent a room in a squatter house ($5/month). Friday was a good day, as I bought five postcards; there was even enough money for him to buy some coffee from a traveling vendor ($0.04 for three cups). He likes it black, strong enough to keep him up at night while he draws new postcards.

I do feel like I was able to help him in one other practical way. One reason Jonathon likes to drink coffee is that the water is boiled, and thus purified. Jonathon, like all the residents of Mwanza, has no access to inexpensive, clean drinking water. Here are his options:

1. Buy bottled water. $0.25/liter is not much for water (Dasani, even!), but when you make about a dollar a day, the cost is prohibitive.

2. Boil water. Using city water, which is probably within 50 yards of his room, and boiling for 15 minutes, Jonathon will have water free of pathogens, but firewood is not cheap, and the smoke has long-term side effects on vision.

3. Walk to the brewery for free, purified water. But it is about a ten mile walk, which is quite hard when you will be carrying gallons of water back. Many people, however, do this daily.

4. Take a chance on city water. Most people do this from time to time. This is a major source of illnesses like typhoid, belharzia, and amoebas. And, over time, these can take a toll on one’s kidneys, eventually leading to kidney failure. (see post from last week). And the medicine cost adds up, too.

I shared with Jonathon one more option: Solar distillation. By refilling a clear water bottle with city water and setting it in a location with strong sunlight for 6 hours, over 99.99% of pathogens are killed. The UV radiation, which penetrates the plastic and radiates the water, does the work for you. Check out www.sodis.ch for more details. Jonathon seemed excited to give this a try. One of many things we will discuss in the future.

(I must give credit to Harding University School of World Missions, especially Oneal Tankersley, who first exposed us to solar distillation)

Thursday, June 15, 2006

Kidney failure and language school.

We are currently staying in the house of one of our teammates while we continue our own house hunting. One of the benefits of staying at the Guild’s house is the presence of Alex, their gardener. Not only does he do a great job with the house (he is the green mamba killer from June 3rd), but he also helps us practice language, and finds time to play with Josiah.

Several days ago, Alex told us of a friend with serious health problems. He had been unable to urinate for 10 days, and was in great pain, so he was on his way to the hospital for treatment.

Alex has not mentioned his friend lately, which I assumed meant that the hospital resolved the issue. I decided to ask him today (Alex doesn’t speak English, so I used a couple words that I knew, plus some body language) about his “rafiki”, expecting the news to be good. Unfortunately, the tone and length of his answer demonstrated a different reality; I found our teammate Jason and asked him to translate for me. This is what I learned.

The hospital provided no help for Alex’s friend, just the bad news that his kidneys had failed. There are no dialysis machines here, so he was free to go and die at any place of his choosing. So he chose to go and consult the “mfumu” (doctor of traditional medicine, or witchdoctor, depending on your perspective). He prescribed some herbal remedy to ease his suffering before his death.

I hope you are not reading this blog immediately after reading yesterday’s dryer diatribe. Tanzania has much greater issues than appliance selection.

I have searched in vain for an answer to this issue. I have dear friends in the States currently sustained by dialysis. Alex’s friend will die never knowing that there is such a thing as dialysis.

Perhaps, one day, all of our friendships will transcend current barriers. At least that is our hope.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

On a lighter note, we have been unable to find a language program in Northern Tanzania that will start within the month. So we have decided to begin individual lessons with a language institute here in town. Dr. Salala, a German immigrant to Tanzania, is known around town as not tolerating language slackers. She will get four hours a week to blitzkrieg Kiswahili into us.

We are currently staying in the house of one of our teammates while we continue our own house hunting. One of the benefits of staying at the Guild’s house is the presence of Alex, their gardener. Not only does he do a great job with the house (he is the green mamba killer from June 3rd), but he also helps us practice language, and finds time to play with Josiah.

Several days ago, Alex told us of a friend with serious health problems. He had been unable to urinate for 10 days, and was in great pain, so he was on his way to the hospital for treatment.

Alex has not mentioned his friend lately, which I assumed meant that the hospital resolved the issue. I decided to ask him today (Alex doesn’t speak English, so I used a couple words that I knew, plus some body language) about his “rafiki”, expecting the news to be good. Unfortunately, the tone and length of his answer demonstrated a different reality; I found our teammate Jason and asked him to translate for me. This is what I learned.

The hospital provided no help for Alex’s friend, just the bad news that his kidneys had failed. There are no dialysis machines here, so he was free to go and die at any place of his choosing. So he chose to go and consult the “mfumu” (doctor of traditional medicine, or witchdoctor, depending on your perspective). He prescribed some herbal remedy to ease his suffering before his death.

I hope you are not reading this blog immediately after reading yesterday’s dryer diatribe. Tanzania has much greater issues than appliance selection.

I have searched in vain for an answer to this issue. I have dear friends in the States currently sustained by dialysis. Alex’s friend will die never knowing that there is such a thing as dialysis.

Perhaps, one day, all of our friendships will transcend current barriers. At least that is our hope.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

On a lighter note, we have been unable to find a language program in Northern Tanzania that will start within the month. So we have decided to begin individual lessons with a language institute here in town. Dr. Salala, a German immigrant to Tanzania, is known around town as not tolerating language slackers. She will get four hours a week to blitzkrieg Kiswahili into us.

Tuesday, June 13, 2006

Can you believe that in a city of over one million people, there are only two appliance stores? And were not talking Best Buy size, either. More like 7-11 size. Not 7-11 prices, though.

I am no economist, but when very few people can afford something like a refrigerator, the prices skyrocket. Or maybe it is because we are accustomed to the leveraged prices afforded us by our superstores and our strength of consumer spending. Who knows?

So, while we can buy a fresh pineapple, mango, avocado, a few tea bags, half a dozen eggs, and a coke for under 2 bucks here in Tanzania, the cheapest clothes dryer… let me rephrase… the only clothes dryer, costs $500.

Ironically, the dryer is only used during the rainy season, about 5 months of the year. Otherwise, clothes go out on the line. Clothes lines, I might add, are quite cheap here.

In other news, Josiah and I traveled to a Tanzanian-run orphanage on the outskirts of town. We accompanied Jason as he set up a two-day stay for our interns. Perhaps we will have an ongoing relationship with this orphanage, assuming we are able to learn Swahili and actually be able to communicate with people.

Josiah seems to think that if you just talk loud enough and point fingers, the message is conveyed. He played for about an hour with some of the orphan boys, but as we all know, boys don’t need to talk anyways. It was funny to hear him yelling, “Y’all come over here”. It will be even funnier to return to the orphanage and hear all the boys practice their good English they learned from Josiah.

I am no economist, but when very few people can afford something like a refrigerator, the prices skyrocket. Or maybe it is because we are accustomed to the leveraged prices afforded us by our superstores and our strength of consumer spending. Who knows?

So, while we can buy a fresh pineapple, mango, avocado, a few tea bags, half a dozen eggs, and a coke for under 2 bucks here in Tanzania, the cheapest clothes dryer… let me rephrase… the only clothes dryer, costs $500.

Ironically, the dryer is only used during the rainy season, about 5 months of the year. Otherwise, clothes go out on the line. Clothes lines, I might add, are quite cheap here.

In other news, Josiah and I traveled to a Tanzanian-run orphanage on the outskirts of town. We accompanied Jason as he set up a two-day stay for our interns. Perhaps we will have an ongoing relationship with this orphanage, assuming we are able to learn Swahili and actually be able to communicate with people.

Josiah seems to think that if you just talk loud enough and point fingers, the message is conveyed. He played for about an hour with some of the orphan boys, but as we all know, boys don’t need to talk anyways. It was funny to hear him yelling, “Y’all come over here”. It will be even funnier to return to the orphanage and hear all the boys practice their good English they learned from Josiah.

Monday, June 12, 2006

mundane

no exciting bus rides, or venemous snakes to report.

is an hour and a half trip to the market, yielding only some eggs, bananas, avocados, and a straw basket exciting?

Everything here is slower. People don't seem to be too bothered by having their electricity cut off for the daylight hours. Negotiating prices on most things you buy isn't an incovenience. People seem genuinely unaware that in America, we can accomplish in minutes what might take a day here.

However, people are pretty bothered when you don't visit their home, or if you fail to offer a greeting as you pass by. This is life here.

Imagine if every time you picked something off a shelf at Walmart, even if just to look more closely, you entered into a conversation with the individual who either made it, picked it, or is reselling it. Price ceases to become first priority. It's all about relationships.

So Sunday AM church went from 10:00 am until 3:00 pm. This included a 2 mile walk to the church, a three mile walk to visit the house of someone whose mother had died this week, where we continued our service, and a mile back home. Everyone was given an opportunity to share any encouragements, thanksgiving, or requests for help. All in Swahili, though we were able to have some conversations on the road in our limited Swahili. No one seemed to mind the walk, or the length of time spent in church.

After all, what is more valuable than relationships, anyway?

no exciting bus rides, or venemous snakes to report.

is an hour and a half trip to the market, yielding only some eggs, bananas, avocados, and a straw basket exciting?

Everything here is slower. People don't seem to be too bothered by having their electricity cut off for the daylight hours. Negotiating prices on most things you buy isn't an incovenience. People seem genuinely unaware that in America, we can accomplish in minutes what might take a day here.

However, people are pretty bothered when you don't visit their home, or if you fail to offer a greeting as you pass by. This is life here.

Imagine if every time you picked something off a shelf at Walmart, even if just to look more closely, you entered into a conversation with the individual who either made it, picked it, or is reselling it. Price ceases to become first priority. It's all about relationships.

So Sunday AM church went from 10:00 am until 3:00 pm. This included a 2 mile walk to the church, a three mile walk to visit the house of someone whose mother had died this week, where we continued our service, and a mile back home. Everyone was given an opportunity to share any encouragements, thanksgiving, or requests for help. All in Swahili, though we were able to have some conversations on the road in our limited Swahili. No one seemed to mind the walk, or the length of time spent in church.

After all, what is more valuable than relationships, anyway?

Wednesday, June 07, 2006

Update…

We have now received all but one of our bags, for which we are thankful. And jet lag is subsiding. I got a good night’s sleep last night…

Part of the reason for the good night’s rest was that I was out of town last night with my friend Lance., a member of the missions vision team at Landmark church, our sponsoring congregation. We traveled to Geita, a small town just 80 miles from Mwanza to do some research.

80 miles is not a long trip in the states. It is much farther in Tanzania. We boarded a bus at 7:30 am. The bus would not leave until it was completely full. Not just the seats (they seated five across, not four), but the aisles as well. When we were crammed to about 100 people, about 3 hours later, we left for the ferry…

Being first class looking people, Lance and I were escorted upstairs in the Ferry boat to meet the Master (aka captain). When he found out that we were American, he asked, “oh, so you are George Bush’s people?” I have dreaded this question for years.

Things got interesting when we were trying to reboard the bus after the bus pulled of the Ferry. This time, 200 people were trying to get on. In a mad rugby scrum for position, nobody making it into the bus, we encountered two pick-pockets (actually, they encountered us.) They got into Lance’s pocket, but didn’t get anything except perhaps a dollat. They tried to get into my cargo pocket, where my camera was, but when Lance warned me to watch my pockets, the crowd and bus crew noticed, and grabbed the suspects.

They pulled me aside as well, to question me about if anything was missing. Now Lance is incredibly strong; grabbing the handles above him, he lifted himself and three women in front of him into the bus. After answering some questions, I decided that window entry would be easier than the scrum. Whereas Lance was gifted with strength, I was blessed with small hips. So up the side of the bus (named Air Jordon… all public vehicles here require a personality), and through the opening in the plexiglass window.

We watched the assembled mob escort the thieves down the road. In truth, I was scared, as thieves here are usually beaten, sometimes even burned to death. While I appreciate being in a society that doesn’t tolerate stealing, I did not want to be associated with the suffering of the two young men. I would rather my pockets emptied. Thankfully, when the bus finally began rolling, we saw the mob at the police station down the road.

While the most interesting part of the journey, it was also the easiest. The next 75 miles were over some of the worse roads in the world. Not only were our bodies being beat to a pulp (several times my internal organs bounced off my tailbone), but that window I climbed through was loose, constantly rattling in my ear. Rattle is an inadequate word; it would have rattled on American roads; it was like a jackhammer on concrete.

It took three hours or so to travel the 75 miles. We had one stop in Sengerema, where vendors were able to sell me an ear of corn, some bananas, a cold bottle of water, an egg, and a goat-kabob. Unfortunately, no ear plugs.

We passed beautiful wetlands filled with beautiful, exotic birds, green mountains, numerous witch-doctor compounds, and tiny clusters of huts populated by the poorest people on our planet.

I could not help asking myself why I was born in America, in the richest one percent of people in the world, a citizen of the richest empire history has ever known. I’m sure the people we passed ask a similar question each day. Yesterday, the question was more likely, “why is that mzungu (white person) on that bus?”.

We arrived late in the day in Geita, a place we had never been, a place where we knew nobody, a place where it was incredibly difficult to find anyone who spoke English. We walked around, observing the town, searching for ways to ask questions and meet people. We found a hotel that prohibited prostitution, with in room toilets and mosquito netting. The room, plus the full dinner we requested, set us back 8000 Shillings. Or 7 bucks. Twice the bus fare. Much more comfortable, though.

We received a wake-up call early in the morning; courtesy of the town mosque. We were able to make the earliest bus, which drove out of Geita as though a volcano had erupted behind it. Apparently, the forward momentum insured that the bus didn’t tip over when it reached near 45 degree slants on numerous occasions. We made it to the ferry in record time, overpassing everything along the road, leaving behind only dust and suspension components.

Anyways, it was an enjoyable adventure, though my body feels like it was left in a dryer for hours, and my ears are still ringing, and it was wonderful to come back home to my wife and sons. Lord willing, future trips like this will be more productive.

And we know a good place to stay in Geita.

We have now received all but one of our bags, for which we are thankful. And jet lag is subsiding. I got a good night’s sleep last night…

Part of the reason for the good night’s rest was that I was out of town last night with my friend Lance., a member of the missions vision team at Landmark church, our sponsoring congregation. We traveled to Geita, a small town just 80 miles from Mwanza to do some research.

80 miles is not a long trip in the states. It is much farther in Tanzania. We boarded a bus at 7:30 am. The bus would not leave until it was completely full. Not just the seats (they seated five across, not four), but the aisles as well. When we were crammed to about 100 people, about 3 hours later, we left for the ferry…

Being first class looking people, Lance and I were escorted upstairs in the Ferry boat to meet the Master (aka captain). When he found out that we were American, he asked, “oh, so you are George Bush’s people?” I have dreaded this question for years.

Things got interesting when we were trying to reboard the bus after the bus pulled of the Ferry. This time, 200 people were trying to get on. In a mad rugby scrum for position, nobody making it into the bus, we encountered two pick-pockets (actually, they encountered us.) They got into Lance’s pocket, but didn’t get anything except perhaps a dollat. They tried to get into my cargo pocket, where my camera was, but when Lance warned me to watch my pockets, the crowd and bus crew noticed, and grabbed the suspects.

They pulled me aside as well, to question me about if anything was missing. Now Lance is incredibly strong; grabbing the handles above him, he lifted himself and three women in front of him into the bus. After answering some questions, I decided that window entry would be easier than the scrum. Whereas Lance was gifted with strength, I was blessed with small hips. So up the side of the bus (named Air Jordon… all public vehicles here require a personality), and through the opening in the plexiglass window.

We watched the assembled mob escort the thieves down the road. In truth, I was scared, as thieves here are usually beaten, sometimes even burned to death. While I appreciate being in a society that doesn’t tolerate stealing, I did not want to be associated with the suffering of the two young men. I would rather my pockets emptied. Thankfully, when the bus finally began rolling, we saw the mob at the police station down the road.

While the most interesting part of the journey, it was also the easiest. The next 75 miles were over some of the worse roads in the world. Not only were our bodies being beat to a pulp (several times my internal organs bounced off my tailbone), but that window I climbed through was loose, constantly rattling in my ear. Rattle is an inadequate word; it would have rattled on American roads; it was like a jackhammer on concrete.

It took three hours or so to travel the 75 miles. We had one stop in Sengerema, where vendors were able to sell me an ear of corn, some bananas, a cold bottle of water, an egg, and a goat-kabob. Unfortunately, no ear plugs.

We passed beautiful wetlands filled with beautiful, exotic birds, green mountains, numerous witch-doctor compounds, and tiny clusters of huts populated by the poorest people on our planet.

I could not help asking myself why I was born in America, in the richest one percent of people in the world, a citizen of the richest empire history has ever known. I’m sure the people we passed ask a similar question each day. Yesterday, the question was more likely, “why is that mzungu (white person) on that bus?”.

We arrived late in the day in Geita, a place we had never been, a place where we knew nobody, a place where it was incredibly difficult to find anyone who spoke English. We walked around, observing the town, searching for ways to ask questions and meet people. We found a hotel that prohibited prostitution, with in room toilets and mosquito netting. The room, plus the full dinner we requested, set us back 8000 Shillings. Or 7 bucks. Twice the bus fare. Much more comfortable, though.

We received a wake-up call early in the morning; courtesy of the town mosque. We were able to make the earliest bus, which drove out of Geita as though a volcano had erupted behind it. Apparently, the forward momentum insured that the bus didn’t tip over when it reached near 45 degree slants on numerous occasions. We made it to the ferry in record time, overpassing everything along the road, leaving behind only dust and suspension components.

Anyways, it was an enjoyable adventure, though my body feels like it was left in a dryer for hours, and my ears are still ringing, and it was wonderful to come back home to my wife and sons. Lord willing, future trips like this will be more productive.

And we know a good place to stay in Geita.

Sunday, June 04, 2006

Our first full day in Tanzania…

It’s late in the night, no longer Saturday but now Sunday, and I am sitting on a foam-cushioned couch in our temporary home. I occasionally scan the room for the mosquitoes flying about—the mini-sized malaria vectors with stealth-like qualities, appearing then disappearing, engaging in psy-ops of the most advanced kind.

They seem to enjoy the sound cover provided by the “Hot Pot” bar down the lane. Every pop song—currently Shania Twain—blasted with volume at both ends of the spectrum: low frequency bass causing the kitchen contents to hum along, and high frequency that musy have a dog whistle effect, as every dog in Tanzania has been summoned to our neighborhood, beckoning them to form a chorus of howls and barks that would put any kennel to shame. Even the dogs here sing majestically.

If only the power company would have rationed the power a little longer, perhaps the night would be still.

The evening cooking fires are smoldering, providing more smoke than heat, but the smell—distinctly African—wafts through the open windows (with screens, of course, to trap the mosquitoes in). The breeze also carries in the dust, aerial dirt that has Charity wishing that she had packed cases of Kleenex in our luggage.

On that subject, we are still waiting for our luggage. Our six bags apparently were less determined to get here than us. Visiting the airport today was hardly confidence-building. Nor was visiting a travel agent in town. He repeatedly said words like “maybe” and “take a chance” and went bug-eyed when I said “six”.

Other highlights of the day included spotting a green mamba snake (google for a picture) between the glass and the screen of our house. Not wanting to put the bizarre promise found in the un-original ending to the Gospel of Mark to the test, we found a Tanzanian, who could swing a two meter pole with the accuracy and power of Barry Bonds at the peak of his cranium-swelled career. “AEYAAAH” he shouted as the wounded mamba rebounded toward him. A shorter stick finished the job. By the time I found Josiah to show him the snake, the mamba was already discarded over the fence, a warning to other trespassing snakes, I suppose.

I have moved under mosquito netting to play with Elijah, confused as a night nurse about day and night. Mosquito netting is our green zone, if you will, offering protection for us, the privileged few. Bono was here recently promoting nets—as he reminds the world often, Africa experiences a tsunami a month, hundreds of thousands dying of preventable illnesses; Malaria being chief.

While I missed Bono’s visit, I did get here just in time to meet Jill. I call her “Hallelujah Jill”. She found us at a restaurant today—us our teammates, the college interns, and Steve, our American friend who works in Mwanza as well.

She found Steve first. Yelled to him from outside the gate. “Are you American? So am I!” (not that her yelling through the gate left any doubt that she was anything other than an American visitor.) “I am here on a crusade… What are you doing tomorrow? Come to church with me!”

Steve is much more mature than I. In fact, he is one of the most Christ-like people I know. Not only is he well-studied (a PhD in intercultural studies after seminary), but he has served in Africa for twenty years, loving and serving his friends here. Everyone feels as I do about Steve; everyone, that is, who has actually taken the time to converse with him before trying to convert him. “I would love to, but I am preaching tomorrow.”

“Hallelujah, a preacher!” (actually Steve trains and equips pastors). Then she boasted (sorry, in my opinion, boasting+a bunch of hallelujahs=boasting… actually, worse than boasting) about the 65 people she saved yesterday (hallelujah!) while praying at a future church site (hallelujah!). And she’s just getting started… 19 days left to go. She would have saved all of us if someone had not beaten her to us (hallelujah!).

Kinda makes me wonder why I am so stressed about learning the language. “Hallelujah Jill” didn’t need to practice cultural sensitivity or learn any Kiswahili, just speak in really loud English.

She did take a break from her crusade to impart her wisdom gained from her three days in Africa with our interns. She concluded with “you will never be the same after your time in Africa.” I wisely added, “And you will never be the same either, after you leave, Jill. Africa, however, will be exactly as you found it”.

Okay, I must admit, these words didn’t come out, but they wanted to. Not only was such a comment mean-spirited, unfair, and not completely true, it also would have prolonged our visit with her.

However, I can not help myself from being skeptical. Because in August I will meet “Praise the Lord” Larry and in September I will meet “Thank you Jesus” Tom. Heroes in a week. Saving some of the same people over and over again. But saving from what? Rwanda was 90% saved before the genocide. I imagine many of the people in the “Hot Pot” right now are saved, spending money on beer and sex instead of school fees for their children. As are the people beating their wives, spreading HIV through casual sex, or returning to the witch doctor to determine who has cursed them, in order to exact revenge against whoever caused their misfortune.

But it is in this reflection that I find my deepest fears. I am not afraid of Malaria, though I am determined to kill that mosquito. Nor am I concerned about our bags or the adjustment to life here, though I know it will be tremendously difficult. What I am afraid of is being a ten-year version of “Hallelujah Jill”, allowing Africa to satisfy my need for significance, without truly helping those around me in a way that will last when I am gone. And I don’t think I will make people cringe the way Jill made me cringe, and I am even more confident that I will not make the impact of Bono, not be considered for a nobel prize or anything. I will end up somewhere in between the two. Just where will be determined in the next ten years. We will keep you posted.

It’s late in the night, no longer Saturday but now Sunday, and I am sitting on a foam-cushioned couch in our temporary home. I occasionally scan the room for the mosquitoes flying about—the mini-sized malaria vectors with stealth-like qualities, appearing then disappearing, engaging in psy-ops of the most advanced kind.

They seem to enjoy the sound cover provided by the “Hot Pot” bar down the lane. Every pop song—currently Shania Twain—blasted with volume at both ends of the spectrum: low frequency bass causing the kitchen contents to hum along, and high frequency that musy have a dog whistle effect, as every dog in Tanzania has been summoned to our neighborhood, beckoning them to form a chorus of howls and barks that would put any kennel to shame. Even the dogs here sing majestically.

If only the power company would have rationed the power a little longer, perhaps the night would be still.

The evening cooking fires are smoldering, providing more smoke than heat, but the smell—distinctly African—wafts through the open windows (with screens, of course, to trap the mosquitoes in). The breeze also carries in the dust, aerial dirt that has Charity wishing that she had packed cases of Kleenex in our luggage.

On that subject, we are still waiting for our luggage. Our six bags apparently were less determined to get here than us. Visiting the airport today was hardly confidence-building. Nor was visiting a travel agent in town. He repeatedly said words like “maybe” and “take a chance” and went bug-eyed when I said “six”.

Other highlights of the day included spotting a green mamba snake (google for a picture) between the glass and the screen of our house. Not wanting to put the bizarre promise found in the un-original ending to the Gospel of Mark to the test, we found a Tanzanian, who could swing a two meter pole with the accuracy and power of Barry Bonds at the peak of his cranium-swelled career. “AEYAAAH” he shouted as the wounded mamba rebounded toward him. A shorter stick finished the job. By the time I found Josiah to show him the snake, the mamba was already discarded over the fence, a warning to other trespassing snakes, I suppose.

I have moved under mosquito netting to play with Elijah, confused as a night nurse about day and night. Mosquito netting is our green zone, if you will, offering protection for us, the privileged few. Bono was here recently promoting nets—as he reminds the world often, Africa experiences a tsunami a month, hundreds of thousands dying of preventable illnesses; Malaria being chief.

While I missed Bono’s visit, I did get here just in time to meet Jill. I call her “Hallelujah Jill”. She found us at a restaurant today—us our teammates, the college interns, and Steve, our American friend who works in Mwanza as well.

She found Steve first. Yelled to him from outside the gate. “Are you American? So am I!” (not that her yelling through the gate left any doubt that she was anything other than an American visitor.) “I am here on a crusade… What are you doing tomorrow? Come to church with me!”

Steve is much more mature than I. In fact, he is one of the most Christ-like people I know. Not only is he well-studied (a PhD in intercultural studies after seminary), but he has served in Africa for twenty years, loving and serving his friends here. Everyone feels as I do about Steve; everyone, that is, who has actually taken the time to converse with him before trying to convert him. “I would love to, but I am preaching tomorrow.”

“Hallelujah, a preacher!” (actually Steve trains and equips pastors). Then she boasted (sorry, in my opinion, boasting+a bunch of hallelujahs=boasting… actually, worse than boasting) about the 65 people she saved yesterday (hallelujah!) while praying at a future church site (hallelujah!). And she’s just getting started… 19 days left to go. She would have saved all of us if someone had not beaten her to us (hallelujah!).

Kinda makes me wonder why I am so stressed about learning the language. “Hallelujah Jill” didn’t need to practice cultural sensitivity or learn any Kiswahili, just speak in really loud English.

She did take a break from her crusade to impart her wisdom gained from her three days in Africa with our interns. She concluded with “you will never be the same after your time in Africa.” I wisely added, “And you will never be the same either, after you leave, Jill. Africa, however, will be exactly as you found it”.

Okay, I must admit, these words didn’t come out, but they wanted to. Not only was such a comment mean-spirited, unfair, and not completely true, it also would have prolonged our visit with her.

However, I can not help myself from being skeptical. Because in August I will meet “Praise the Lord” Larry and in September I will meet “Thank you Jesus” Tom. Heroes in a week. Saving some of the same people over and over again. But saving from what? Rwanda was 90% saved before the genocide. I imagine many of the people in the “Hot Pot” right now are saved, spending money on beer and sex instead of school fees for their children. As are the people beating their wives, spreading HIV through casual sex, or returning to the witch doctor to determine who has cursed them, in order to exact revenge against whoever caused their misfortune.

But it is in this reflection that I find my deepest fears. I am not afraid of Malaria, though I am determined to kill that mosquito. Nor am I concerned about our bags or the adjustment to life here, though I know it will be tremendously difficult. What I am afraid of is being a ten-year version of “Hallelujah Jill”, allowing Africa to satisfy my need for significance, without truly helping those around me in a way that will last when I am gone. And I don’t think I will make people cringe the way Jill made me cringe, and I am even more confident that I will not make the impact of Bono, not be considered for a nobel prize or anything. I will end up somewhere in between the two. Just where will be determined in the next ten years. We will keep you posted.